| Back to Back Issues Page |

|

|

Bangkok Travelbug August 10 The Travelbug’s homecoming July 30, 2010 |

| Hello

1950s – Childhood memories As a boy one of my happiest moments would be an outing with my father to the Esplanade, the park by the waterfront at the mouth of the Singapore River. It was a chance to roam around the well-kept park and gaze out to sea at the ships anchored off-shore.

The Esplanade Singapore 1950s, the Fullerton Building (then the General Post Office) and Anderson Bridge are in the background

The Esplanade Singapore 2010, the Fullerton Building (now Fullerton Hotel) and Anderson Bridge are still there. The rest of the skyline has changed beyond recognition. Late one afternoon, during an outing to the Esplanade, father stopped in front of a monument. It was the Lim Bo Seng Memorial, father explained. This was his story. Table of contents 1930s – War clouds gather Singapore in the 1930s, like many South-East Asian cities, was buzzing with Chinese nationalism. The Second Sino-Japanese War had started with the Japanese attack and occupation of Manchuria in 1931. Sporadic fighting continued until 1937 when Japan attacked the Marco Polo Bridge outside Beijing and the Japanese offensive intensified. By the end of 1937, Nanjing surrendered to a fate of mass executions, rape and plunder. In Singapore a young well-educated Chinese businessman from a well to do family answered the call of duty. He organized boycotts of Japanese goods and raised money for the China Relief Fund among the Chinese to support the war against Japan.

Lim Bo Seng, photo taken off his tombstone Lim Bo Seng was born on 27 April 1909 in Nan Ann, Fujian province, China. When he was 16, his family migrated to Singapore where he studied at Raffles Institution and later the University of Hong Kong. A Kuomintang member, Lim was a fervent supporter of the Nationalist Chinese cause. Table of contents 1941 – World War II comes to Malaya At dawn on 8 December 1941, the 25th Japanese Imperial Army under Lieutenant General Tomoyuki Yamashita landed in Kota Bahru in Malaya, Pattani and Songkla in southern Thailand. The Malayan campaign was launched. Back in Singapore, Lim mobilized Chinese labour to support the British civil defence effort, essential services and island defence works.

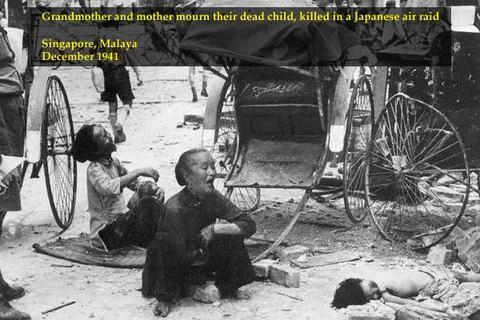

An indelible image that sears the memory. Courtesy of World War II Data Base But British defences in Malaya crumbled within 55 days before the relentless Japanese onslaught. With the 25th Japanese Imperial Army at her doorstep in southern Johore by 31 January 1942, Singapore’s days were numbered, 15 to be exact.

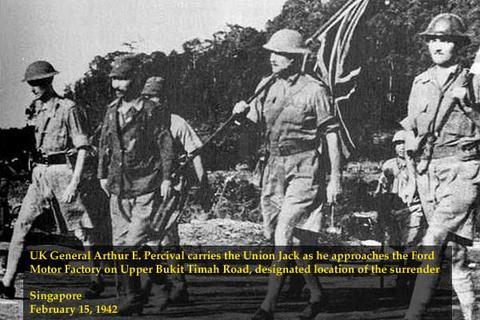

The Japanese officer is Lieut-Col Sugita, 25th Japanese Imperial Army who spoke English. The British officer on the extreme right (carrying the white flag) is Capt Wild who spoke Japanese. Courtesy of World War II Data Base For his anti-Japanese activities, Lim was a marked man on the Kempeitai (Japanese military police) black list. He had to flee. On 11 February 1942, four days before the British surrender, he kissed his wife and seven children goodbye and left Singapore. He would never see them again.

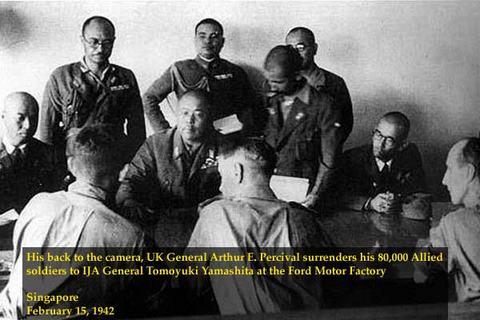

Today a condominium occupies the grounds of the Ford Factory. The factory has been preserved as a historical monument. The table on which the surrender document was signed is in the Australian War Memorial, Canberra. Courtesy of World War II Data Base His escape route took him through Dutch Sumatra, Ceylon (Sri Lanka) and finally to India. There he joined the British intelligence service and underwent military training. Lim then went to Chong Qing in Nationalist China to recruit Malayan Chinese to join the British Force 136, the Far East branch of Britain’s wartime Special Operations Executive. This organization was responsible for subversion, sabotage, espionage and organizing local resistance in enemy territories. On the night of 2 November 1943, a Chinese junk rendezvoused with a Dutch submarine off the coast of Pulau Lalang, west of the Perak river mouth. Lim Bo Seng, who was on board the submarine, was about to be infiltrated into Japanese occupied Malaya to set up an intelligence network to prepare for the British invasion. The man waiting in the Chinese junk to take him ashore was Chin Peng, later the Secretary General of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM). Lim negotiated a truce between the Communists in the Malayan People’s Anti-Japanese Army (MPAJA) and the British from Force 136 operating behind Japanese lines. The Communists were far more established and organized in Malaya and the British agents needed their help for movement and safe bases. Lim also worked undercover to organize the intelligence network in the Perak area. Unfortunately on 27 March 1944, Lim was stopped at a Japanese checkpoint in Gopeng and arrested. He was imprisoned in Batu Gajah Prison in Perak, where he suffered interrogation, torture, illness and deprivation. He finally died on 29 June 1944 at the age of 35. Table of contents The post-war years Some records claim that Lim was betrayed by Lai Teck, the treacherous Secretary-General of the Communist Party of Malaya (CPM) who worked for the Japanese and later for the British as well. After the war, several members of the CPM were betrayed by Lai Teck to the British during the Malayan Emergency, the armed struggle between the Communists and British in Malaya. Chin Peng who took over leadership of the CPM records in his memoirs that Lim was betrayed by his own Kuomintang man who was involved with a dance hall girl in Ipoh. This indiscretion compromised the identities of the other Kuomintang agents who were arrested too. The remaining Kuomintang agents had to remain in hiding and were unable to contribute to the intelligence network. The British were left to depend on the Communists whose organization was still intact. This arrangement must have worked well for Chin Peng the Communist leader was awarded the Order of the British Empire (OBE) after the war. Whatever the case, Lai Teck met his just end in 1947. When the traitor was spotted in Surawong Road Bangkok, the Malayan Communists got their Vietnamese counterparts in Bangkok to track him down. Their Thai comrades were assigned to bring him in. The three-man Thai team pounced on Lai Teck and during the struggle he was strangled. They bundled his body in hessian cloth and dumped him in the Chao Phraya River later that night. In Chin Peng’s words, “He met with his final judgement”. Lim Bo Seng was posthumously promoted to Major-General by the Nationalist government of China. After the war Tan Chong Tee, Lim’s Force 136 comrade and fellow prisoner, informed Lim’s family of his death. Lim’s remains were exhumed from the shallow grave in the jungle near Batu Gajah Prison and brought home to Singapore by his wife and eldest son. On 13 January 1946 after a grand funeral procession, Lim was laid to rest with full military honours in a grave in MacRitchie Reservoir Park. The memorial over the grave was erected on 27 June 1957.

Lim Bo Seng’s grave, MacRitchie Reservoir Park Singapore 2010 Ten years after his death, on 29 June 1954 the Lim Bo Seng Memorial on the Esplanade was unveiled in his honour by Commander-in-Chief, Far East Land Forces Sir Charles Loewen.

Lim Bo Seng Memorial – Esplanade Singapore 2010 It was getting dark in the Esplanade by the time father finished his story. The street lights were coming on. Across the street in the Padang, courting couples huddled in the darkened field. We got into father’s black Ford Prefect and drove home in silence. Table of contents Singapore, 9 August 1995 – 1800 hours The flight of three Super Puma medium utility helicopters in arrow head formation flew over the parade. Slung below the leading chopper a huge weighted down national flag of Singapore fluttered in the wind. Tight formations of A4-SU Super Skyhawks, Northrop F5s and F16 Fighting Falcons jets flew past in a deafening roar drawing gasps from the expectant crowd on the Padang below. In the wake of the supersonic booms, the Black Knights made their dramatic entrance with a daring display of aerial acrobatics in their red and white A4-SU Super Skyhawks. Half a kilometre away along Nicoll Highway, the mobile column of AMX-13 tanks, M 113A1 armoured personnel and artillery carriers revved their engines. It was time to roll. The march past was about to commence. The column rounded the northern edge of the Padang and entered St Andrew’s Road. Lieutenant-Colonel Lim Teck Yin stood in the turret of the leading AMX-13 tank as the mobile column drove slowly along St Andrew’s Road towards the steps of City Hall. As the column approached City Hall, the main guns of the tanks dipped in salute. In 1942 victorious Japanese troops marched, almost swaggered, down this road after the British surrender of Singapore on 15 February. On 12 September 1945, Allied troops took the same route for the victory parade and the surrender ceremony in City Hall. Admiral Lord Louis Mountbatten, Supreme Allied Commander South-East Asia Command, stood before these very steps and led Allied troops assembled on the Padang in three cheers to the King on the day Singapore was liberated after three and a half years of Japanese Occupation.

Memorial to the civilian victims of the Japanese Occupation 15 Feb 1942 – 12 Sep 1945 inaugurated on 15 Feb 1967 for the civilians who lost their lives. The exhumed remains of the victims are buried beneath the memorial. Had Lim Bo Seng been alive on that sunny August afternoon in 1995, he would have been 86. The sight of his grand-son leading the mobile column past the steps of City Hall would surely have brought a surge of pride in the old soldier’s heart, and tears to his eyes. Old soldiers know that feeling. “You must not grieve for me. On the other hand you should take pride in my sacrifice and devote yourself to the upbringing of the children. Tell them what has happened to me and direct them along my footsteps.” Lim Bo Seng’s farewell letter written in jail to his wife Choo Neo, the letter was found with his wartime diary which the British returned to his wife after the war

View from the hillock where Lim Bo Seng’s grave is located, overlooking MacRitchie Reservoir “Tell them what has happened to me and direct them along my footsteps.” Table of contents Postscript The Padang is a huge field in front of City Hall. It’s a feature in many major cities and town in British Malaya and Singapore where national events, parades, festivities and games take place. This feature remains to this day. Many ex-members of the Communist Party of Malaya, including Chin Peng, are residing in southern Thailand today. Some of them have received Thai citizenship. During a citizenship ceremony in late 2003, the new citizens pledged their allegiance before a portrait of HM the King. Recently it was reported on Thai TV that Chin Peng had expressed a wish to visit his hometown Sitiawan, Perak in Malaysia. His application for citizenship was rejected in 2003 and so were several appeals to the courts. Similarly, some ex-members of the Barisan Sosialis (Socialist Front), a defunct political party in Singapore, are also living in southern Thailand where they are now Thai citizens after years of being in limbo. In mid-2009 an ex-Barisan member in his 70’s and suffering from cancer visited Singapore with his Thai passport. He got to see his hometown, a very different Toa Payoh again after 46 years. On his way out of Singapore, the immigration officials warned him not to come back again. He didn’t. He died in December 2009. His last wish to see his country of birth again was fulfilled; a country that didn’t even want him back. May he rest in peace. Table of contents My Thanks My thanks to Jason McDonald of World War II Data Base for the old photos of Singapore during World War II. I am grateful to my friends from Singapore, Albel Singh, Frank Singam, Gerry de Souza and Yuen Chee Mun for refreshing my memory on details of that parade in 1995. I must also thank my Thai friend for sharing the story of her father with me. It’s sad that Singapore has done this to her father. Table of contents

Next month Ao Manao the battle of Prachuap Khiri Khan 1941 If you enjoyed reading this e-zine, please forward it to a friend. If you received this from a friend and found it interesting, please subscribe at Bangkok Travelbug. What you think of the Bangkok Travelbug? We love to hear from you What other subscribers have said Till next month then. Eric Lim Stay updated with what’s new at Tour Bangkok Legacies. Copy the link below and paste it into your Google Reader, NetNewsWire or your favorite feed reader. https://www.tour-bangkok-legacies.com/tour-Bangkok-legacies.xml If you use My Yahoo! or My MSN, head over to my home page and click on the button for your favourite Web-based feed reader. Visit our home page at Tour Bangkok Legacies. Copyright@2008-2009 Tour Bangkok Legacies All rights reserved |

| Back to Back Issues Page |